This article was written by Dominic Mein (Year 12 from Logan Park High School) and Kenzie Drake (Year 12 from Otago Girls' High School). They are both in the Student Leadership Team of Town Belt Kaitiaki, with Dominic writing about the overall project and Kenzie contributing the section about forest stratification research. Published September 2025.

What is Town Belt Kaitiaki?

Town Belt Kaitiaki (also known as TBK) is a Dunedin-based, student-led group founded in 2017. It features students from most of the schools nearby the Town Belt, the large nature sections that exist within Dunedin.

TBK currently has students from twelve schools, including six secondary, two intermediates, and four primary schools, as well as four early childhood centres.

TBK’s goal is to preserve the natural beauty that is the Town Belt, all while raising awareness about it.

My name is Dominic and I'm currently in Year 12. I've been involved with TBK on and off since 2020, helping to represent Balmacewen Intermediate (2020-2021) and Logan Park High (2022-present). Many others have been assisting TBK for similar or if not longer lengths of time. Outside of the students, various volunteers have helped out throughout the life cycle of TBK. It’s not an exclusive club, but a community effort.

Kaitiaki is a te reo Māori word, which means ‘guardian’ in this context, and TBK is proud to fulfill the role, empowering young people to protect the Town Belt. We have a role model site in the form of an area nearby Robin Hood Park. Within it, we have weeded, planted, surveyed, and trapped, among other things. TBK has also been involved in various projects such as community events, surveys, and other such activities.

My greatest personal achievement during TBK has been the nurturing of kōwhai seedlings. Five years and a lot of work have created a dozen or so kōwhai trees from nothing more than humble seeds. One of these trees has now been planted in Logan Park High School, which you can see in the photo on the left.

I am also currently working as the Secretary, note taking meetings whenever I’m there, which isn’t always ever due to forgettance or scheduling issues. There are other roles too. It is a group effort. I’ve been to various TBK overnight hui, with 2025’s providing a stunning wetlands view of the night sky.

Community Education at the Science Festival

This section has been written by Kenzie Drake, Year 12 student at Otago Girls' High School.

On Wednesday the 2nd of July, the Town Belt Kaitiaki students ran a stall at the annual New Zealand International Science Festival. The NZISF’s mission is to inspire and engage people of all ages and backgrounds about the importance science plays in our daily lives and the positive difference it makes. Through this opportunity, we got to engage with people from all different backgrounds and teach them about what the TBK program is all about and some of the work we’ve been up to this year. The focus of our stall was around how light affects plants in the Town Belt, specifically in terms of stratification.

Stratification: How sunlight affects the forest

Stratification is the vertical layering of plants due to the availability of certain abiotic factors, the main one of which being light. Have you ever noticed when you're going on a nature walk through your local forest or Town Belt, how trees tend to grow to different heights? That’s stratification in action.

%20%20(250%20x%20300%20px)%20(12).jpg)

Plants need to find their own niche, or special place to grow. If they didn’t, we’d have much less variation in our ecosystems. Plants tend to fall into around 4 distinct strata layers: The emergent, canopy, subcanopy, and shrub layer.

Each layer falls underneath the last in order of decreasing height as well as light availability. This means that trees in the emergent layer (i.e. Rimu) will have exposure to the full sun and can grow over 30 meters whereas those in the shrub layer (i.e. Horopito) will have very limited light and are no more than 5 metres tall.

The layers in forests form because two species competing for the same limited resources cannot coexist at stable population levels, one will always out-compete the other. When shifting to gather their required resources in a different strata layer, plants no longer need to fight as hard to survive.

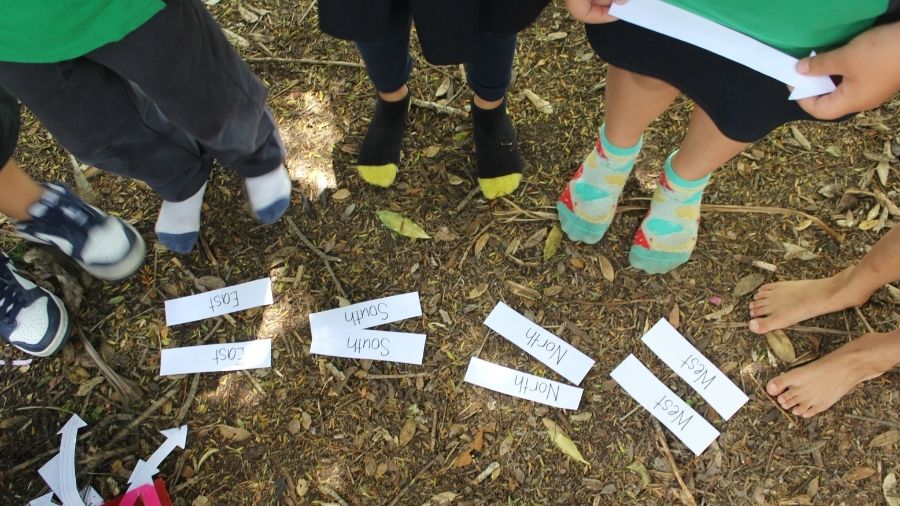

At the Science Festival stall, we created activities to get tamariki to engage with the idea of stratification in a fun, hands-on way.

Our most popular activity was a collaborative build-a-tree project, where each child made a paper leaf, with designs ranging from rainbows to realistic rubbings. Throughout the day, these leaves were added to a large paper trunk on our display wall, slowly transforming into a vibrant, collective tree, a physical reminder of how every small contribution helps an ecosystem flourish.

We also took our teaching beyond the stall by roaming the mall armed with a holey umbrella and luxometer. When held over someone’s head, the umbrella showed how sunlight filters through the forest canopy, with the holes letting in “sunbeams” while the rest remained shaded. This simple demonstration helped people visualise how different forest layers get different amounts of light, in hopes to make a complex ecological concept more memorable and fun.

%20(900%20x%20350%20px)%20(11).jpg)

Understanding how our forest ecosystems work is key to protecting them. The Town Belt isn’t just a random patch of greenery in the middle of the city; it’s a living, breathing taonga. A home to countless species that rely on the delicate balance of the ecosystem. When we take the time to learn about these systems, we start to see how every tree, fern, and insect plays its part.

The more people, especially young people, understand about the biodiversity in their own backyard, the more they feel responsible for protecting it. The concept of kaitiakitanga reminds us that we are not the owners of the land, but guardians for the generations to come. Sharing science in this way isn’t just about facts, it’s about passing on a philosophy of care and respect.

That’s why it’s so important to have rangatahi at the heart of these conversations. When young people lead and share knowledge, it creates a ripple effect. It inspires peers, whānau, and communities to feel connected to the living systems around them.

As someone who has grown up with the Town Belt in my backyard, I’ve learned that looking after it starts with understanding it. In the words of a teacher whose advice I’ll never forget, “If you know the names of the trees, you’ll notice when they’re gone.”

Mā tātou katoa te taiao e tiaki. It is up to all of us to care for the environment.

Related Programmes and Stories

Town Belt Kaitiaki is part of a group of student-led conservation projects around the country based on the Collaborative Community Education Model (CCEM). Developed by educators, communities and ākonga, starting with Kids Restore the Kepler in Te Anau and Kids Greening Taupō, the CCEM model is based on years of experience and research and is now used to guide local collaborative projects in many locations around the motu. Current projects also include Te Ara Taiao in Taranaki and Kids Enhancing Tawa Ecosystems (KETE) in Wellington.

You may also like to read some of our related Spotlights:

Rākau | Trees in our Learning Spaces

Exploring Biodiversity through Statistics Investigations

Young Peoples’ Voices in Community Decision Making

Acknowledgements

Huge thanks to Dominic, Kenzie and the Student Leadership Team, along with the Town Belt Kaitiaki education coordinator Maureen Howard, for contributing this article.

All images have been provided with permission by Maureen and the TBK students.