Main Image: Gracie Keenan, ākonga, Te Kura o Mātā (April 2023)

Article written by Orini Rokx-Taratu and published September, 2025.

This article reflects on my learnings as a young Māori student teacher, and a ‘researcher’ navigating teaching and learning during crisis, climate change, whakapapa, wairua, and intergenerational resilience.

Harakeke pupuri whenua

Harakeke that holds the land

I ahu mai ahau i Te Uranga o te Rā, i te pārekereke o Marotiri maunga. Ko Mangahauini te awa, ko Te Whānau a Ruataupare te hapū, ko Ngāti Porou te iwi. He hononga hoki āku ki ngā iwi o Ngāti Awa, Ngāpuhi, ā, Samoa hoki. Ko Orini Rokx-Taratu tōku ingoa.

The whakataukī above emerged from a community research project I was part of post-Cyclone Gabrielle. Being an 18-year-old “coasty girl” during the cyclone recovery, I was considered the perfect candidate for a research position - according to one of our community leaders - who encouraged me to take on a rangatahi researcher role, interviewing whānau on the impacts during and after Cyclone Gabrielle in the Tairāwhiti region. Te Weu Charitable Trust presented me with the opportunity to contribute to the recovery phase in a way that utilised, and further developed, the mātauranga that I had as rangatahi, as ahikā, as raukura of kura kaupapa Māori, and as a mokopuna who was raised by the hāpori.

Harakeke pupuri whenua was inspired by one of the findings, specifically a response by one of the participants who shared a solution to erosion. The participant, Les Ahuriri, stated “we need to plant more harakeke”. Uncle Les, as he’s known, talked about how harakeke have strong roots, a lot of leaves but no wood. He currently plants and maintains harakeke at the back of his property due to losing over half of his section to erosion over his lifetime.

When I was invited to take on this researcher's position, I was also just beginning my first year of study towards a Bachelor's degree in Primary Teaching, which was my plan B, and initiated after challenges resulting from prior weather events. When the cyclone struck my tūrangawaewae, Tokomaru Bay, it cut us off completely.

This article reflects on my learnings as a young Māori student teacher, and a ‘researcher’ navigating teaching and learning during crisis, climate change, whakapapa, wairua, and intergenerational resilience.

Growing Up in Tokomaru Bay

The image of the pā harakeke has stayed with me since that interview with Uncle Les: the rito, or young shoot, sheltered by the outer leaves and nourished by deep roots planted deep into the whenua. That symbol of mokopuna growth and well-being sustained by the care of whānau, and being nourished by te taiao - these were exactly the experiences I had growing up in Tokomaru Bay.

Just as the harakeke cannot stand without its roots, we too cannot stand without our whenua.

Tokomaru Bay is a small rural town, about 90km north of Gisborne, famous for its paua pies and being one of the first places to see the sun - Te Uranga o te Rā. I was educated by aunties and uncles at a small kura kaupapa Māori, Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Mangatuna, tucked inland between Tokomaru Bay and Tolaga Bay.

At kura, we learned heaps about kai - digging in the māra, collecting mimi noke (worm pee) for the plants, and just getting our hands dirty.

Then there was ‘Kai Atua’ day - where only food that relates to atua Māori was allowed. Kai Atua days still hold strong for me, highlighting just how many of us were dependent on packaged food. It was convenient, yes, but our teachers would always remind us that the rubbish goes straight into the bin, and then into our whenua - not to mention the number of artificial ingredients fueling our bodies.

Even as kids, it made us think harder about the choices we were making and the impacts that they had - this was my first formal climate learning experience.

Our teachers also taught us how to gather kai from the moana. One day our hauora teacher took us diving for pāua – I still remember being thrown against the rocks, determined to hold my breath long enough to impress Matua Daryl and to try to get bigger paua than my friends. These are the rich experiences that informed my ‘researcher’ perspective. Ironically, these were also the experiences we lost due to the extreme weather events taking place on the Coast.

%20(900%20x%20350%20px)%20(12).jpg)

The Coast, as they call it, the mighty East Coast, was once known for its long, beautiful summers. But heavy rains became constant, awa and moana turned murky, and what was once normal slipped away. The blame game about forestry, farming, industries, and even the whenua itself was relentless. For me, it revealed how deeply the impacts on land are tied to the impacts on life, mauri, and wairua.

Shifting Climate, Shifting Whenua

These changes reminded me of the strength of the pā harakeke. My time at kura kaupapa was like growing at the centre of a thriving harakeke. I was the rito, sheltered by the outer leaves, my kaiako, cousins, and whānau. Daily life was steeped in te ao Māori: karakia each morning, waiata, and everything done in te reo.

Our classroom stretched beyond four walls into the bush, the moana, and the whenua. Through pūrākau, hītori, and waiata I gained not just mātauranga but also a deep sense of belonging, safety, and identity. Just the way we interacted with each felt natural, felt māori.

In 2023, during my first year of teacher training, I became a teacher aide at Te Kura o Māta, a small farm kura 37 kilometres inland from Tokomaru Bay. My aunty was the principal, my mum the teacher, my siblings and cousins the students, and I was the student teacher. Surrounded by bush, paddocks, and the rumble of logging trucks, tamariki learnt by exploring. Curiosity, or mahi tutu haere as we call it, was never shut down - it was celebrated and became the spark for learning.

One day, tamariki investigated possums brought in after a hunting trip. A ten-year-old ākonga, already skilled at providing kai for his whānau, led the activity with pride. He showed his peers how to skin the possums and examine their puku. Together they discovered what the animals had eaten and began asking how carrots ended up in their puku - turns out they were getting into the compost.

More importantly, though, they had kōrero about why possums were harmful to the ngahere. Their questions grew into a conversation about kaitiakitanga. What might seem confronting to others was, for them, normal, māori, and deeply tied to their identity.

Tikanga was just as evident when the kura axolotl died. Without adult direction, tamariki organised a tangihanga. They prepared the space, held a poroporoaki, and buried their mokai as a whole school. It was instinctive. Tikanga wasn’t something they performed; it was part of who they were.

These experiences reminded me that every tamaiti is a rito, nurtured by tikanga, whakapapa, and whānau - roots deeply planted into the earth, holding the land together with their potential and their aspirations.

At Māta School, tamariki flourished because curiosity led their learning, their ao Māori shaped their worldview, and everyday life was valued as mātauranga. As I step into the role of a kaiako, I come to the realisation that I remain the rito - still growing and learning - but I am also becoming an outer leaf, wrapping around ākonga, encouraging their curiosity, and protecting the values that will guide them forward.

%20(900%20x%20350%20px)%20(13).jpg)

Mate Whenua, Mate Tangata

While the cyclone revealed the resilience of our people and the opportunities to turn crisis into a learning experience, it also exposed the deep wounds that climate change-driven weather events leave on the wairua of people. Tokomaru Bay already faced many challenges before the cyclone – poor health and education statistics, high rates of addiction, and the weight of social and wellbeing issues. Living there was already hard, yet those same challenges also strengthened our bonds as we navigated them together. When Cyclone Gabrielle cut us off from essential services, those existing inequities collided with the impacts of climate change, compounding our struggles.

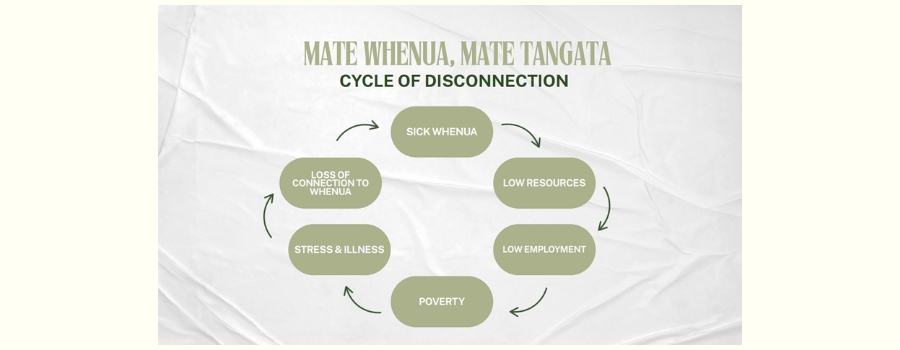

From these experiences, I began to develop the concept of Mate Whenua, Mate Tangata: The Cycle of Disconnection. This cycle reflects what I observed and lived through – that a sick whenua, damaged by industry and climate change, leads to low resources and low employment. These conditions then fuel poverty, which in turn drives stress and illness. In survival mode, whānau become disconnected from their responsibilities to the whenua, as the urgent need to get by overshadows the collective responsibility to nurture it.

This disconnection further sickens the whenua, returning us to the beginning of the cycle. It is a trap that continues unless it is interrupted – a cycle where the state of the whenua and the state of the tangata are inseparably bound.

Breaking free from the Mate Whenua, Mate Tangata cycle requires more than survival, it requires reimagining education, resilience, and connection to whenua in ways that interrupt the destruction.

For me, the cyclone was both a moment of devastation and a turning point. It forced me to see that learning in crisis is not confined to classrooms or theories but emerges from everyday acts of resilience, grounded in tikanga and whakapapa. In the face of disruption, tamariki and whānau became the teachers, and our lived realities became the curriculum.

This is where I began to understand that climate education must move beyond abstract lessons into the lived experiences of communities navigating disruption together.

Cyclone Gabrielle: Learning in Crisis

Reflecting on my experiences during and after Cyclone Gabrielle, and on the everyday teaching and learning that unfolded in Tokomaru Bay, I have come to see climate education differently. The recovery showed me that resilience is not built through theory or crisis-response alone, but through lived practice, tikanga, and intergenerational knowledge. The lessons below are not abstract ideas, they come from real experiences of tamariki, whānau, and communities navigating the impacts of climate disruption.

1. Resilience grows from everyday life

During recovery, when the weather had settled, tamariki milked cows, cared for chickens, planted in māra kai, and observed beekeeping. None of these activities felt “special” to them, yet in the context of climate disruption their importance was clear.

These everyday practices, passed down by whānau, showed tamariki that self-sufficiency is possible. They are more than chores, they are taonga tuku iho that anchor resilience in daily life.

2. Mātauranga is our strongest resource

When kaumātua, parents, and aunties and uncles stepped in to share knowledge, whether about kai gathering, land care, or tikanga, it became the curriculum. For example, at the wharf, tamariki followed tikanga without being prompted, returning small fish to Tangaroa. Such moments reveal that mātauranga held by whānau is powerful teaching that ensures culture and values continue naturally.

3. Curriculum must reflect lived reality

Climate change is not something to be taught as a separate “topic.” It must be woven into daily learning. Feeding animals, fishing, preparing or planting kai all became science, history, and health lessons when seen through the lens of climate resilience.

For tamariki, this made climate education real and meaningful, not distant or abstract.

4. Curiosity builds confidence

When tamariki investigated possums after a hunting trip, or when I took them fishing at the wharf, their natural curiosity led the learning. Questions about pests became kōrero about kaitiakitanga. Handlines at the wharf became lessons in ecology and tikanga. By encouraging curiosity, we helped tamariki grow into confident, critical thinkers.

%20(900%20x%20350%20px)%20(14).jpg)

5. Tikanga anchors us during disruption

Tikanga wasn’t taught as a separate subject, it lived within tamariki. When an axolotl died, they instinctively organised a tangihanga. At the wharf, they returned fish to Tangaroa. In both crisis and calm, tikanga grounded tamariki and gave them a way to make sense of events. It is our cultural compass, guiding responses to disruption.

6. Whakapapa reminds us of our responsibilities

Tamariki are more than students; they are ritō of the pā harakeke, nourished by whakapapa and whānau. Understanding their ties to whenua and taiao helps them recognise their role as kaitiaki. This was clear when tamariki questioned why possums were harmful to the ngahere - connecting their learning back to protecting whakapapa and future generations.

7. Equity in roles strengthens communities

Fishing taught me how important it is to widen who can be the provider. Traditionally, tamariki saw their dads and uncles as the ones to bring kai from the moana. When I, as a wahine, caught kahawai with my siblings and later invited rangatahi to fish, it shifted that norm. It showed tamariki that wāhine can be gatherers too, strengthening community capacity and resilience.

8. Past mistakes must inform planning

Landslides, erosion, and flooding were not simply caused by the storm; they were outcomes of historical decisions; deforestation, colonisation, and planting species that weakened the whenua. If these realities are not acknowledged, we risk repeating them. Teaching must use these mistakes as lessons to shape better decisions in the future.

9. Recovery is wairua as well as practical

During the cyclone recovery, gumboots and roadworks were vital, but so were karakia, waiata, and whanaungatanga. Tamariki saw that healing the land also meant healing people. Recovery was as much about collective spirit as physical rebuilding, reminding us that wairua cannot be separated from resilience.

10. Education is preparation, not reaction

The greatest lesson was that resilience must be built every day, not only in times of crisis. Fishing, gardening, or caring for animals gave tamariki tools to face disruption with confidence. If education waits for the next disaster to teach resilience, it is already too late.

Learning must prepare tamariki for the future by making interdependence, agency, and identity part of the everyday curriculum.

During the cyclone recovery, the most powerful learning for our tamariki came through everyday acts of resilience. Whānau offered their time and mātauranga to ensure our ākonga know what living self sufficiently could look like. Tamariki helped in māra kai, learned how to milk cows, cared for chickens, and observed beekeeping.

None of this felt “special” to them because these were normal parts of life, passed down naturally by aunties, uncles, and kaumātua. Yet in the context of climate disruption, these practices revealed their true value. They were not just skills; they were taonga tuku iho.

IMAGE on right: Kohanui Raihania, Te Uranga o Te Ra Rokx-Taratu rātou ko Natiailewaikahu Rokx-Taratu - ākonga from Te Kura o Māta (March 2023)

Carrying the Mātauranga of our Tīpuna Forward

Uncle Les taught me more than just planting harakeke. He taught me about the value of intergenerational learning. Harakeke Pupuri Whenua reminds us that the rito, the centre shoot, cannot thrive without the shelter of its outer leaves. In the same way, our tamariki cannot flourish without the protection of whānau, whenua, and mātauranga which in turn protects whānau, whenua, and mātauranga. Cyclone Gabrielle showed us the strength of this interdependence, but it should not take a disaster for us to live this way.

Connection to te taiao doesn’t have to mean growing kai or fishing every week - especially in cities. It can be as simple as listening to te taiao, noticing weather patterns, feeling the warmth of the sun, or watching the tides shift and responding accordingly.

These are everyday lessons too, teaching tamariki that the outdoors is not only normal, but critical, and that the whenua speaks if we take the time to notice. Once we make that connection to te taiao, we make that connection to ourselves and to our tīpuna.

Harakeke pupuri whenua - harakeke that holds the land, harakeke that holds us - carrying the strength of our tīpuna into the future for our mokopuna.

%20(900%20x%20350%20px)%20(15).jpg)

Acknowledgments

All images (except RNZ acknowledged image) and videos have been provided with permission by Orini Rokx-Taratu.

You may also like to watch our webinar series from Youth Week 2025

Part One: Mate Whenua, Mate Tangata, with Orini Rokx-Taratu and Santino Morehu-Smith

Part Two: Panel Discussion with taiohi from Future Unity and Papa Taiao